- Home

- Howard Cunnell

The Painter's Friend Page 2

The Painter's Friend Read online

Page 2

I’ll take three packets.

Paid for the papers and the soup. When I opened the door, and the thundering sound of the water was once more amplified, he was coming around from behind the counter with a floor brush in his hand. An economy of movement, like a man once confined to a small space with other men.

I held the door open for an angry-looking man with a shaved head, and huge eyes so dark and unlighted they appeared black.

The woman with him was younger and taller, with short hair and a very upright posture, as though she were carrying with care something I couldn’t see. She wore a red cotton thread around her wrist. Like me, both of them had thick mud over their boots and up to their knees.

Neither of them had used the scraper, but the hard-edged man didn’t correct them as he had me. In fact he seemed happy to see the woman.

Perseis, he said, hello again. And Gene.

The angry man glared at the storekeeper but either he didn’t notice or he didn’t care. He was still looking at the woman, who wore the same long black coat as my late night water watcher, and I was sure it was the woman I had seen.

She turned and looked at me with eyes so deeply blue they were nearly violet.

I wonder if we might borrow Anthony for a moment? she said.

I was just leaving, I said.

In the yard a red phone box. I had a phone, an ancient Nokia, but signal on the island was unreliable, especially at the moorings. I’d put the Nokia in a drawer and almost never thought about it.

Tied to the little jetty was a big gleaming boat. The water was thick with fallen leaves, and the broken whiteness of the boat’s reflection.

The high fence around the yard was locked in the sandy-haired man’s absence. When it was locked you couldn’t buy gas. No gas meant no cooking, no hot water and only a battery lamp or candle for light.

It was bad enough for just a couple of days but I bet there were people who went without gas for weeks at a time until money was found from somewhere. Black winter nights, rain in pools on the partly frozen, umber-coloured ground, and points of candlelight in the black shapes of windows softly rising and falling as the barge rocked gently in the freezing water.

Kids came running into the yard, dirty-faced, whooping and shouting, carrying home-made bows and arrows and wearing oversize jumpers and boots, parakeet and crow feathers in their long hair.

A boy, older, maybe twelve or thirteen by his height, wore a wolf mask, the thick rubber kind that you wear like a balaclava. The kids all screamed when they saw me, a monster to run away from. When they screamed there came back from a place unknown to me a rattling volley of barking, a woman’s voice calling the kids home.

The couple came away from the boatyard. In the falling light the woman’s face was so clear I thought I might see my reflection in it if I ever got close enough.

The man lifted the gas canister onto his shoulder. A tremor rippled over his body in a continuous wave and then stopped. He stood up straight.

I hate that geezer, the man said, he’s a posh cunt.

The woman with the rare violet eyes didn’t answer, but raised her head and looked up at the huge sky that was almost all black dark now, starless but stars would come, with the last traces of light disappearing in the west.

Thump thump thump across my deck. My outside neighbour going ashore. An old man in warmer looking clothes than any I’d brought with me. Lives on a narrowboat, talks to himself. Loudly. Breath visible. Seen that kind of reefer coat in old war films. Up periscope. The fast white lines of torpedoes. The destroyer sunk. Survivors into the lifeboat. Desperate men adrift.

The coat is navy, double-breasted. Thick as a blanket. Looks ancient, stiff enough to stand by itself. Wide collar turned up so that under his dark wool hat I couldn’t see much of the old man’s face. Dark canvas trousers, ancient shin-high sea boots. Bloody thumping over my deck first thing. Boat sinking and rising with his weight. Old man so he goes slowly, but he doesn’t hesitate or hold on. A beaten track long before I got here. Thump and then waiting for what feels like forever for the next. Thump. Like a diver. Bottom of the sea. Lead boots.

There’s nobody living on the barge between us, which is under a black canvas that collects rain and is sometimes plastered with ash leaves and bird shit.

Winter cold. A fight to get warm in the morning. To crawl out from under all the blankets and piled clothes and relight my fire. Waking dreams. Evelyn Crow at the point of my gun. My fist. Am a great painter. Everybody says so. But Crow won’t tell me where my paintings are. Despite his broken teeth, the blood on his suit. So I hit him again. And again.

Thump, thump.

Though often it’s the smell of freshly ground coffee drifting across the river air from the old man’s narrowboat that wakes me before first light. Strong enough to cut through the solid planking of my boat and into my head. Fall for it every time. I am a rich and famous painter. In a white bed in a high white room with French windows open to my blue sea. A distant white sail. The windows framed by sweet and vivid roses. Downstairs my fair but suntanned young lover, wearing my gift of a gold necklace, is making coffee. I fall back asleep knowing she’ll wake me.

Thump. Thump.

Useless hard-on and no coffee.

The disused engine is down there, beneath my neighbour’s boots. Stilled machinery and trapped dead air. A lot of hollow space. The boom of boots on deck reverberates across the still river. Birds should rise in alarm from the trees, but I’m the only one it seems to bother.

The bitter cabin air is almost visible in flavoured waves. Cold woodsmoke edged with damp. Just enough left of the coffee smell to piss me off.

Put more clothes over the ones I slept in. The stove still warm if I’m lucky. Embers. Bank it up quick. Make a Nescafé still wrapped in blankets. Smoke a roll-up. A good morning. When I have gas and tobacco and firewood and enough instant in the jar.

The canvas wrapping the barge between us is only sometimes thick with leaves and bird shit because after heavy winds or a period of rain the old man climbs up and clears the leaves and shit and water.

A goat on a rock. Not falling off. Deliberate movements. Steady. Got a brush with a taped handle. Ridiculous. Time he’s finished he’s got to start again.

The old man of course takes pains about clearing his own narrowboat of leaves and bird shit, but he clears the empty boat before his own, most of which is also winterized with a protective canvas covering.

The exposed cabin doors and stern are detailed in strong colours: red white and blue with orange decking. There are painted roses and a castle on the cabin doors and, especially during the worst of the black winter days, the painted stern is often the only source of brightness I can see. Makes me wonder what the rest of the boat looks like under the tarp. Likewise the old man’s thick outer garments protect him from examination.

If he owns both boats that would make him king of the island. Am I supposed to clean my boat? If it’s some kind of rule everybody else is ignoring it.

Each morning involves an appraisal of conditions as I build a new fire. Supplies. Money. Weather. State of river, light, mind. Voices in the head – the drunk who lives inside trying to trick me into making a mistake.

Then the old man comes thumping across the inside of my head.

A pirate with two wooden legs.

Slowly the boat warms and the cabin air blurs and smokes once more. I like to go up to the wheelhouse with my Nescafé and roll up. Begin a new drawing. Looking up from my work at some fast movement outside – too late to see a bird passing, or the reflection of a bird passing on glass or water. Cormorants, kingfishers and a single grey heron hunt on the river undisturbed.

Rare tugs pull barges stacked with freight.

Across the river were a number of large white houses, with big gardens leading down to private jetties. The river, the unknown quantity of all that cold water, made the houses further away than they looked – about half as far away as the bridge downstream. Whic

hever direction the powerful river currents were travelling, you’d have to navigate them to make the other side. There was no straight line across. It was against the far bank of the river in front of these houses, a soft-edged stretch between river and sky, forest green and brown and gold, fringed with willows, that I once saw the outline of a police launch patrolling the jetties and little inlets.

If the old man hasn’t crossed before I get up there he’ll see me in the wheelhouse when he does. Cloth bag under his arm that looks stuffed with papers. Talking to himself. So I have to wait for him to cross my boat before going up to the wheelhouse.

Standing completely still in the gloomy cabin with the plywood doors to the wheelhouse closed. Gulls flying up the river in heavy traffic. The boat creaking against the fenders. Waiting means I’m not free so I could easily come to hate the old bastard. Despite the fire some part of me was cold all the time.

I think he wants to talk.

Looked into the wheelhouse and saw me.

Coming back late. Wherever he’d been had knocked the stuffing out of him. Crept back with no noise. Looked cold and wet. Sore with age. Stiff coat holding him up. A full shade darker it was so thick with rain. Keeping tight hold of his bag. You’d almost say he was smaller than before. Seen through the light of my lamp, the water-streaked window, the night and the rain. Face of hard planes and angles.

No sounds but the rain beating on the roof of my boat. A man seen through a series of obscuring lenses. Relieved only by low and patchy light, the waxing moon. Couldn’t see the colour of his eyes, only that they were not clear.

Seen through the gaslight.

Wavering and yellow.

Tired. Long day.

But you didn’t look like that when you left.

Like a drunk pulled up by the cops and fighting to look sober.

I blanked him and was pleased with myself. Turned away until I heard him slowly crossing over the empty boat between us. Soon as he left I drew him. An apparition.

Stomp across my bloody boat every morning and see where it gets you.

The boat’s empty because nobody wants to live next to him. That was the obvious explanation.

Man owned the other boat or he was a lunatic, abroad at all hours, climbing over boats like a robber on the rooftops of a sleeping town.

Giving me no peace.

Had to find out.

Next time I needed supplies I’d ask the sandy-haired man.

Had to wait my turn. A couple in puffa jackets wet with rain, and dirty trainers, loaded groceries onto a wheelbarrow. Sacks of rice and flour. Packs of water, tinned food. Bulk buying. Smart because cheaper.

The man wheeled the barrow out.

I held the door open.

Who is my neighbour?

Blue eyes went somewhere else, came back to me. Hesitated. I asked him for tobacco. Put it next to the small pile of other things I was buying. Watched him make up his mind.

What he told me didn’t have to be the truth.

John Rose, he said.

And was he a sailor?

A merchant seaman. When he was young. A machinist for donkey’s years. Factory closed. Redundancy. Here ever since.

The storekeeper looked at his dirty floor and grunted. Wiped the counter clean of something only he could see.

What should I know about him? I said.

The old man’s wife died, he said. Leave him alone.

Rain streamed down the big wheelhouse window. I couldn’t see much beyond the stern. Some debris being rushed downstream. I wasn’t going outside. My fire was lit and I had a cup of coffee. I made and smoked a liquorice paper roll-up.

From my supplies I had brought out a sheet of butcher’s paper, and I was drawing mushrooms I’d collected in the forest. Later I planned to make a mushroom tea with honey. See if anything happened haha. The butcher’s paper held the line of a sharp pencil really well.

First smoke makes you need a shit. Finding the portaloo full, I swore. Should have done this yesterday. Lifted the bowl from the container, and finding the cap behind the toilet I screwed it on. Strong temptation to empty the shit into the river.

Then again the sound of a couple of gallons of piss and shit going into the water would be unmistakeable. When I rented the boat Mrs Whitehead had told me it was sanctioned practice to push the offender in after his shit if you caught him at it.

Carried the heavy container up the steps to the wheelhouse and out into the rain. Carefully. Rain fell on the water, drummed on the ground and the container, and against the waterproof that covered my head and body, making the material crackle. Downstream the bridge was made invisible by the weather. Every boat that could had a fire lit, but the tang of woodsmoke barely cut through the rain.

From the west of the island I heard the faint, complaining sound of an electric sander or angle grinder. I walked on the towpath towards the forest, falling rain visible against the dark treeline. Past a barge I hadn’t noticed before.

A fair woman was emptying the contents of the bucket she carried into the river. She was wearing a gabardine raincoat dark with rain, and what looked like bright gypsy trousers tucked into an old looking pair of black boots.

When she saw me looking I didn’t say anything, though I may have grunted a little when I shifted the shit container to my other hand, the contents sloshing around inside.

The ash tree canopy protected me from the worst of the rain and softened the noise of its falling. Towards the cesspit the forest became dark. There was grey wet light at the edges of my vision.

The opening of the cesspit was covered in stained planks. I kick-flipped the boards clear and stepped back. Thousands of flies droned below. The rain dampened down the worst of the stink, but I could still taste shit at the back of my throat. I placed the container horizontally on the slippery boards so that the sealed top was over the opening, and leaning over the pit, I unscrewed the cap. I raised the base of the container and turned my head as the contents began to empty and fall loudly into the wet pit. As was always the case I felt some splashback on my hand. I washed my hands and rinsed out the container at the standpipe.

When I came out of the forest the woman in the raincoat was still emptying the bucket over the side of her boat. Dirty water, it looked like. The kid with the wolf mask was carrying a saucepan by the handle with both hands. Looking hard at the pan, his tongue sticking out between his teeth. The woman paused to look at me with grey eyes, wiping the rain from her face. Long tied-up hair the colour of wet straw. I placed her in her early thirties. Somebody who loved her might call her pretty, but the woman would have a hard time believing it. Red half-moons of pinched skin under her eyes. The gabardine was not waterproof. The kid walked in slow motion across the wet deck, balancing the full saucepan.

Shit run? the woman said.

Shit run, I said, raising my empty container.

The kid emptied his saucepan and raised it at me. Rain made a hard pinging noise against the steel pan.

I went aboard my boat. Left my waterproof and boots in the wheelhouse. The need to shit had come on strong again. I fitted the container to the seat and filled the flushing mechanism with water.

Afterwards, I went up to the wheelhouse and got back into my wet things, swearing.

At the barge the woman was holding a squeegee mop over the side, using the lever on the mop to wring out water. There was a long and tall grey dog standing motionless on the bow in the rain, watching me. I stood my ground, unsure around dogs. I couldn’t see the wolf kid.

What’s the problem?

Water in the hold, she said.

Need a hand?

I showed her the bucket I’d taken from the shower stall.

You’re OK, she said, thanks. It happens. We’ve got it.

Sure?

She looked up at me, clear-eyed, standing with her feet apart on the deck, holding the mop by her side.

Sure, she said.

Danny, she called to the invisible kid, time to go. G

et your bag, your lunch.

Every morning the kids crossed the weir to a waiting school bus.

Leave the mask behind, the woman said.

The dogs barking and howling in the night had to be monstrous. Huge-headed and scarred. Straining at thick chains sunk into heavy concrete blocks, and snapping their jaws at anything that came near. Ground littered with old shit and bones. Their cries dragged me out of my dreams of revenge and glory. I didn’t know where the dogs were and that made it worse.

They live in the forest, the woman on the barge, Stella, had told me.

Wild dogs?

There’s a camp.

Not your dog?

Joins in sometimes. Gets excited.

Right. And the people?

Yes, she said, there’s people up there.

What kind of dogs are they?

Mongrels?

The kind that look friendly and then bite you, I said, or the kind that just bite you straight away?

I went up on deck, listening to the dogs. The ash trees were bowed in the wind and rain. It would be hard living up there.

I’d lived outside. From when I was a kid. Wandered through England, sleeping in empty houses and parks, other people’s fields, falling in with the ravers and travellers, free movement and free festivals, a loved-up kid drawing by a fire, waking in the smoky blue dawn to riot cops charging the camp, breaking heads and kicking over blackened pots and dirty mattresses. Locked up again, fighting, taken from prison to the nuthouse because they don’t know what to do with you, sectioned, a blue rubber mattress and enough Thorazine to knock you out for years, the unit shut down, cuts, released to shuffle through identical sodium-lit shopping centres in different towns, spending what gets thrown at you on knockout drugs and drink that tastes flammable as you suck it down. A bloated lump of meat in a filthy sleeping bag, pissed-on cardboard boxes, an easy target for the lagered-up steroid boys, you don’t feel the kicks until the security guard moves you on at first light, standing well back because you stink so bad you shit yourself you cunt?

Everywhere I went men smoked outside pubs where it was always happy hour, or stood in the street clutching plastic bags never full enough of tins of strong lager, looking like they wanted to fight the daylight.

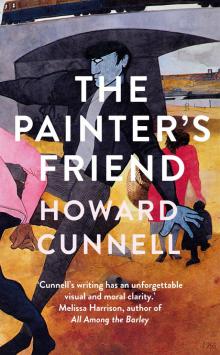

The Painter's Friend

The Painter's Friend