- Home

- Howard Cunnell

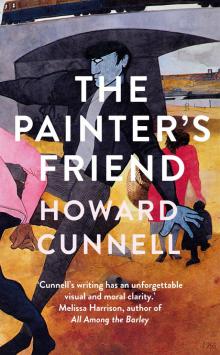

The Painter's Friend

The Painter's Friend Read online

Contents

The Painter’s Friend

Acknowledgements

for John Healy

I was in earnest always or I was nothing

John Clare,

John Clare By Himself

She doesn’t run, Mrs Whitehead said. You can’t go anywhere.

Late October, maybe November. Hadn’t kept track.

Evelyn Crow once said I had invented the idea of myself as an outcast but here I was. Leaving the city. Doors locked behind me. Ghosting through the picture-loaded streets, past a man out cold in a doorway. Cardboard sign illuminated apple yellow. The sign so closely packed with text I couldn’t read a word. A long story. Nobody to read it but himself.

The bare bulbs of the market stalls lit the fruit in bonfire colours. Meat on hooks was heavy ruby stillness, white borders. A corn-coloured dog appeared from the darkness under a wooden barrow. The dog held a lettuce leaf in its mouth, and the green shimmered against the faded black of the barrow’s painted wheels.

Businesses boarded up, except for the pawnbrokers and bookies, the legal highs and tattoo places, and junk shops selling the past. The stuff desperate people sold for food money or their dead left behind. Suits worn to a shine, broken-down shoes, old uniforms, service medals, rings of beaten gold.

The Spitfire pub stood at the end of a row of gutted houses. Pale men half seen moving in and out of the dark spaces inside.

The heavy pack’s canvas straps cut into my shoulders and the sweat was wet on my back.

Stopped at a hoarding. The wide barrier stood in front of what used to be a skatepark and was now a building site, for flats no one living round there now could afford. The hoarding was collaged with graffiti, carvings, tribute band posters, a missing person flyer.

Gill, a pretty girl with a shiny face. Ribbons in her hair. Sunday clothes. Missing. She might have been fifteen in the photo. The picture was old. She wouldn’t look like that any more.

A repeated pattern framed the girl’s picture, made from stylized hearts and what looked like a bird with its head turned backwards and something, a pearl maybe, in its mouth.

Ran my hand over the hoarding, bumpy and hard with the thick glue paste that covered it, a dimly reflective surface in which moving traffic, people, me, were hinted at in muted and fleeting colours.

Got knocked into, sworn at, forced to move along.

A barefoot man with dark matted hair and a rope for a belt said:

Go and come back.

Sky the colour of wet concrete.

What you’re doing, Crow had said the first time we talked, looking through my drawings, pencil and felt tip, charcoal, crayons, my paintings on hardboard and used canvas, might have some purchase.

Tall, angular, dressed in black. Scent of fig and mint from his freshly shaved head. Glasses with blood-red frames, behind which dark eyes were sharp and clear. Snowy skin that looked cold to touch. Holding a drawing to the light. Humming. A man looking at a treasure map and trying to decide if it’s the real thing. Charcoal study of ex-miners on a beach in Kent. Crow smiled at me. The drawing trembled, held between the thumb and forefinger of his right hand. Knotty wrist, stones under the skin.

I knew who he was.

Crow had made a ton of money for Burke Damis, whose huge, larger than life paintings sold for the kind of money that makes the news, and were shown in the best galleries, though not lately. Hyperreal, they called his work. I thought it was flash. A one-trick horse with a castle in California. Vineyards. Damis had produced no new work in years, but thanks to his assistants the stuff kept being churned out. After Ariel Galton, who had once been married to Damis, drowned herself at sea, Crow became her biographer with Burke’s approval. Together the two men made another fortune from the handful of abstract paintings Galton had left behind. Ariel Galton was my mentor, though we never met, let alone spoke.

Human fallout, Crow said, still looking at my work. I like it. There might be a window.

Voice like honey. Loving Crow’s voice was one of a thousand regrets that made the roaring in my head.

Tell me there’s a painting of this, he’d said.

The miners. Six men grown old. Black suits thin as paper. Shoes with worn heels. Hadn’t worked since the strike. Blacklisted. Thirty years. More. Rolled cigarettes no thicker than matches.

In the drawing four men were making a ring for two of their companions who were about to fight. A deserted car park overlooking a beach in Kent. The squared, imagined ring, its dimensions and limits, seemed summoned from shared memory. Understood by the men standing like knife edges at its corner points. The barechested old fighters even seemed to lean against ropes that weren’t there. The beach, the grey corduroy sea and banked sky, going on forever.

The landscape dominates, Crow said, but I can’t help thinking about these men. You have to really look to see them. Who are they?

I told him.

What happens to people like that? Crow said.

Crow promised me my first big painting show. All new pictures. Worked for two years solid, thinking about nothing else. Last chance. Be sixty in a year, making pictures for most of that time. Still burned for them to say I was good. Crow said I was. Promised to make it happen. Let myself dream about the red-tiled, whitewashed house in the sun I’d finally be able to buy, with a terrace framed by hibiscus, stone steps leading down to the Mediterranean. In the shade of the flowered arbour, a young woman with a long brown throat places fresh wine on the sun-worn table.

Picasso in old age was said to give young women he wanted to get to know figurines made of solid gold – a likeness of the artist with a great big whanger. All I wanted for the rest of my life was to look at light patterns moving on endless blue water.

The money didn’t come through. Suspected Crow of lining his own pockets. Fixing the prices low without telling me. Using proxy buyers. Getting my work cheap.

They said I attacked him with a tyre iron or a large kitchen knife or both. Armed with a machete. Crow said he’d been too terrified to remember, but that I’d definitely had a weapon. Crow said: Knowing Terry’s past, I was in fear of my life.

It’s true I threatened to kill him but I was unarmed.

I’d been homeless, locked up and even sectioned. On my own since I was a kid. Who were they going to believe, me or the powerful gallerist, who once confessed to me his surprise he’d not been knighted?

The word went out. Don’t buy or show his paintings. Don’t reply to his texts. Don’t take his calls or answer the door. Don’t let him in. I couldn’t get near them.

If my name was ever mentioned in public, it was always associated with violence.

Crow said he had supported me for two years, and that sales of my work had not even covered his expenses.

The unsold paintings were given to Crow for costs and damages I could never hope to pay. The experience of painting had been one of happy work. Filled with the light I was making.

I’d taken many photos but the images had none of the power they once had in my mind.

Went back to work on the rollers and brushes. A building site is a place of constant piss-taking, but I was lower than a beaten dog. My co-workers left me alone on my painter’s scaffold. From up there you’d hear a hundred things worse than anything I was supposed to have said to Evelyn Crow. You’d hear laughter, too.

But the work dried up and soon I was on the out again. Read about the boat on the noticeboard of the artists’ studio where I was sleeping on the floor unknown to anybody.

Needed to move fast or I was gone.

When I said I wanted to rent the boat for a year the owner jumped at it.

She just sits there in the winter ordinarily, Mrs Whitehead said, and of course we�

�re out of the country by then. Without somebody to pump the bilges and light a fire her condition deteriorates terribly.

Promised not to dump my shit in the river but always use the cesspit, and the boat was mine. So long as the mooring fee was paid by direct debit every month. I hoped to last the year, but if I was too free and easy with the money I’d saved I’d have no chance.

She doesn’t run, Mrs Whitehead said. You can’t go anywhere.

The sky became a sweeping wash of tangerine and coral pink. Infills of deep purple that would soon dominate. A fairground sky.

Night beat me to the river. From out of the darkness I could see the falling mid-air whiteness my directions had said to head towards. River water falling over the weir that led to and from the island. Beyond this whiteness was a darker, high mass that was the forest of ash trees that gave the island its name.

The iron weir crossed over high and fast running water. Lights were studded in the pilings, the illumination they gave off flaring up at me so that I made the crossing in a dense white glare, with the deafening sound of water I couldn’t see falling all around. I felt my way across the walkway, freezing spray hitting my face, my boots clanging on the iron.

At last I stepped onto the island, into the restored and quiet dark. Didn’t have a torch though I was told to bring one in the neat, handwritten note that was sent with the keys.

There are a few paths, Mrs Whitehead had written, but mostly the ground is rough, overgrown, and there are many exposed tree roots you can twist an ankle on or worse. There are no medical services.

She had said the moorings would be ahead of me as I left the weir. Hidden by the trees whose presence deepened the darkness I walked in, and whose top branches I could hear high above me on the river wind, making their shell-to-the-ear sounds. Rising up around me was the thick smell of wet soil.

The boats were in lines of three, and by chance my boat was in the front rank, nearest the riverbank.

A woman stood in the bow of what looked like a barge somewhere towards the back of the line, wrapped in perfumed smoke from a held bundle of incense sticks. Visible breath a mark of early winter. Face and hands white against a dark, too-large overcoat worn draped over the shoulders like huge wings. Cropped head. A penitent figure who could or who could not be said to be looking for patterns in the river, but who might just as well be watching other patterns on the screen of mind.

Thin columns of woodsmoke showed above several boats. There were lights showing, and like the smoke that told of fires, or the absence that didn’t, when lights showed or went out here would always mean something. Somebody new is coming. A big man with a bigger pack, moving slowly, heavy boots.

A converted lifeboat from a retired White Star liner, Mrs Whitehead had explained, with a large wheelhouse grafted on to her. All planes and curved surfaces of wood and glass. Crossed the gangplank and stepped on deck and the boat pushed away and pushed back under my boots.

Found the light switch in the wheelhouse and the suddenly visible river around the boat, the island bank on my near side, the starboard side of the boat next to mine, the interior of the glassed-in wheelhouse, all became golden and navy-edged.

At waist height next to the wheel and control panel were makeshift plywood double doors, padlocked, that opened to steps down into the living quarters. There I found a small galley, a two-ring gas cooker. A jar of instant coffee, enough for a couple of cups, no other supplies. A settee covered with a worn red blanket. Gas lamps were mounted on the bulkhead. A stove. Small pile of cut wood.

The dampness in everything was a quality of thickness in the air. I stopped noticing it after a minute. The bow was behind a hand-sewn patterned quilt that functioned as a curtain, where a bed made thick by blankets and other covers took up all the space.

Every movement produced another beneath me.

Everything was squared away, Mrs Whitehead calling in a favour, or paying somebody. Coffee was a bonus I hadn’t expected, and I set about making some.

No drink, I said to the loud voice inside my head. You’re not having any.

Didn’t stop me searching the boat to make sure there wasn’t a bottle on board.

In time I made a smoking fire. Ate the food – bread and cheese – I’d brought with me. Lit the gas lamps and turned them down low. Didn’t know how much gas I had. Took a cover from the bed and wrapped it around me, looking into the fire and trying to become used to the lack of solid ground beneath me. The cabin became a moving space of varying and competing patterns of light and dark, as though I was being held in the process of submersion, and at any moment would continue my descent.

Next day I went walking with my drawing book to better understand where I was.

To the south, a few hundred yards downstream, was a three-arched bridge faced with rose-pink brick and what I believe was Portland stone.

Not a reinforced bridge carrying the recognizable forms of cars and vans and lorries towards the city, but a sequence of shining ovals both in and out of the water, while above these forms sometimes passed at irregular intervals an indecisive pattern of stalled or moving coloured marks.

Found a chest-high pile of large stones crowned with yellow leaves. The top stone was heavy, smooth to touch and patterned in marine shades of grey and white. It was not of the forest. The stone and its companions looked like stones you might find at the bottom of the river, and I thought they must have been gathered from the island foreshore at low tide and brought to this place. Not all at once but over a period of years.

This was in a clearing from where a number of rough paths radiated. I wondered if the stones were a marker, though no direction was indicated or, as far as I could tell, needed on so small an island.

Michael was written in scuffed and faded black marker on the big bottom stone. I wondered who Michael was, and if what I was looking at was his work, as nearby I found groups of leaves that seemed recently to have been made into patterns: coronas, thick fans and huge circles all made from leaves of varied brightness.

Almost tripped over the wreckage of a Mariner four-stroke engine abandoned in the forest. Everything was slick and wet. As Mrs Whitehead had warned me there were tree roots everywhere. I wondered about wild animals. Twice I heard what I thought was a shotgun. Crows rising from the trees each time.

A deflated orange football sat on a plain wooden picnic table that was almost submerged by lichen. A small dinghy filled with water tied alongside a boat so consumed by mould it looked derelict. Flat-tyred bikes under dirty tarps among the trees. Burst sandbags. A blue water butt on its side. Ropes in great quantity lined the riverbank, coiled or hung from tree branches. A cat’s cradle of weathered ropes held the bankside boats to found or made moorings. Scaffolding poles thick with rust and warped planks were jury-rigged to make gangways to the boats.

Sound travelled a great distance. The soft hollowed-out scoop of a paddle making a cut through the water. I could hear the drops of water falling from the blade to the river in soft sequence, but in the velvet light of early morning the canoe with its single pilot was only a dark, drifting smudge.

I would not dump my shit into the river. I would keep to myself, and keep a tight lid on my anger.

Though I believed I could turn some of them into a healing tea, I did not collect the red winter berries that grew along the riverbank for fear that they would poison me.

Next day I walked into the boatyard store with mud on my boots. The sandy-haired man behind the wooden counter looked at me with no expression on his face. Mouth a straight hard slash. Dirty blue eyes. Some scar tissue. Fair eyelashes almost transparent in the muted light that came through the small, high windows. Thick smooth hands. Clean-shaved, the skin on his fair cheek inflamed, sensitive. Close-fitting blue shirt. Wax jacket. Not tall, but he filled his clothes with hard edges.

The floor swept as clean as it could be.

Scraper outside, the man said.

Missed it. Sorry.

Didn’t need an enemy. We

nt back out and stamped and scraped my dirty boots as best I could, jamming my bare hands under my armpits. Wet and freezing. Getting dark.

Three crows sat on the chain-link fence surrounding the yard. When one hopped sideways the others followed, keeping the same distance between them. Blue and orange gas bottles stood in ranks, shining wet with rain.

The sandy-haired man hadn’t moved. No heating except for the blower I could hear behind the counter.

Help you?

The boatyard and store were on the other side of the island from the moorings, the same side as the broad-crested weir and lock that linked and separated the island to and from the mainland.

The weir meant that the water level at the moorings was several feet lower than the boatyard side. The river also had a significant tidal reach. At low tide my boat seemed almost to scrape along the bottom, and everything on the island seemed high up and far away. At high tide we rose on the brimming river, almost level with its banks.

Part of the store was given over to a chandlery, for trade with the owners of whatever moving boats called on the island.

Tins of food face out so that their labels showed. Tomatoes, sardines, ravioli, beans, soup. I picked out a minestrone. The label of the tin behind was face out, in line. Jar of Nescafé. Same. The bread tray was empty. Have to come earlier. Have to come back with a list. Work out a budget. Down here things were limited. Things, including money, would run out.

Sign on the door: no credit.

Liquorice papers?

What I’d come in for though it was a long shot.

He had tobacco back there and a box of different papers. The last of the smokers. No customs stamps. Couple of boxes of shotgun shells next to the tobacco.

I wondered if the shots I’d heard in the forest came from his gun.

Something of the fighter or ex-mercenary about him. Saw him crouched on a contested airstrip, cool under small-arms fire.

How many?

The Painter's Friend

The Painter's Friend